In The Things They Carried, author Tim O’Brien wrote about a platoon of American infantrymen in the Vietnam War and described the unlikely items these men included in their kit. One wears his girlfriends’ stockings around his neck, believing they have the ability to protect him. The reader learns also, through a series of vignettes, that that these Soldiers carried emotional weight, along with the physical weight of objects large and small. I one story that happens years after the war, a member of the platoon acknowledges how the weight of the memory of his buddy’s death has affected him.

This reflection is about the things that letterpress printers don’t carry.

Letterpress printers do not generally keep a lot of physical things on their person, other than what they choose to place in the pockets of their aprons. There,once can always find one or two stubs of a pencil, some sort of note pad or scraps of writing paper, a pair of tweezers, a broken or misshaped gauge pin, the odd Linotype slug or nearly dry tube of makeready paste. From my father, I learned the habit of stowing my pica gauge (a 12-inch metal ruler) in the back pocket of my pants, which continues to annoy me on the rare occasions when I have to sit down in the print shop. Invariably, the gauge catches on the back of the chair when I stand up and, bending until its spring-like action reaches a certain point, is pried from my pocket and is then flung several feet across the shop.

Mary and Jim DiRisio at The Norlu Press, Fayetteville, North Carolina (2014). We are wearing our printer’s aprons and holding composing sticks while we compose lines of text from individual types stored in a California Job Case. The rack is of my own design, made simply from plywood and two-by-fours. I glued and screwed sections of oak quarter-round moulding to form the rails that support each type case. This design takes up a little more space than traditional (and now antique) racks, but as the rails extend forward approximately six inches further than the type cases, the printer can extend the cases to reveal their entire contents without removing them from the rack. It is still a good idea, however, to take Hobie’s advice and extend slightly the case directly below the one in use, so that it does not “accidentally” fall off its rails and pi the entire case of type.

Rather than carrying them, most printers keep their trade’s necessities within arm’s reach of the place where they are working, and usually in one of three main areas: the composing, imposition and press area.

For composition, or the setting of the individual types into lines, one usually finds a fairly simple arrangement that is based on a rack of multiple type cases, a composing stick and an assortment of leads and slugs. Often, the top of the rack of cases is canted at an angle, which allows the printer to remove a type case from its place in the rack and position it approximately chest-high. This enables the printer to see and reach all of compartments for each individual piece of type, including the lower case “k,” which is at the very top row of compartments and often hidden from view and reach if the case is not removed from its rack.

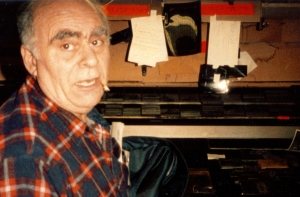

Lewis “Hobie” DiRisio at Norlu Press, Fairport, New York (circa 1986). This was the composition area of the shop, and behind him, against the wall, the long black rack of leads and slugs is visible. Below the leads and slugs, in the bottom right corner of the photo, numerous standing formes and sorts of types occupy the work surface real estate that was ideally suited for the type case that contained the types one was composing. The toothpick in my dad’s mouth made my mom crazy, but most of us liked it better than the cigar butt that it replaced.

By the time I began my informal apprenticeship in my dad’s shop, that slanted worktop surface was covered with so many “standing” formes (jobs one expects to print again) and “sorts” of types (incomplete fonts, sometimes only a few types borrowed from another printer for a specific job) that I didn’t have the luxury of using it to make composition easier. Consequently, I became adept at peering over the tops of the higher racked cases and squatting in awkward poses to get down to the lower cases. The fact that those standing jobs included, in 1977, menus for long-closed local restaurants that included 55-cent Highball cocktails and sorts of types with names of people whom I had never known did not seem to matter. For my dad, it was important to have them on hand, just in case (and he would have fully intended that pun.)

As with O’Brien’s Soldiers, not everything a printer carries, or uses, is a physical item. Anyone who prints carries memories of how he or she learned the craft, of the circumstances that made one love the unnameable aroma of ink, old lead, solvents and wood that permeates letterpress shops, and of the people along the way who shared their knowledge. For me, it is impossible to separate my memories or current understanding of printing from the image of my dad, Lewis “Hobie” DiRisio, who established the original Norlu Press and was a lifelong letterpress printer. Initially, this included the image of him with a stub of a cigar (usually unlit) in his mouth, but as I spent more time in the shop, the cigar eventually gave way to a toothpick when he gave up cigars “cold turkey,” as he would say. While I learned enough about printing to take it up again as a hobby after being away from it for twenty-five years, I learned so much more about who I was, where I came from and that family is the foundation of being.

That is what this printer carries.